Unraveling the mystery of running shoes carbon plated running shoes part II

Published:

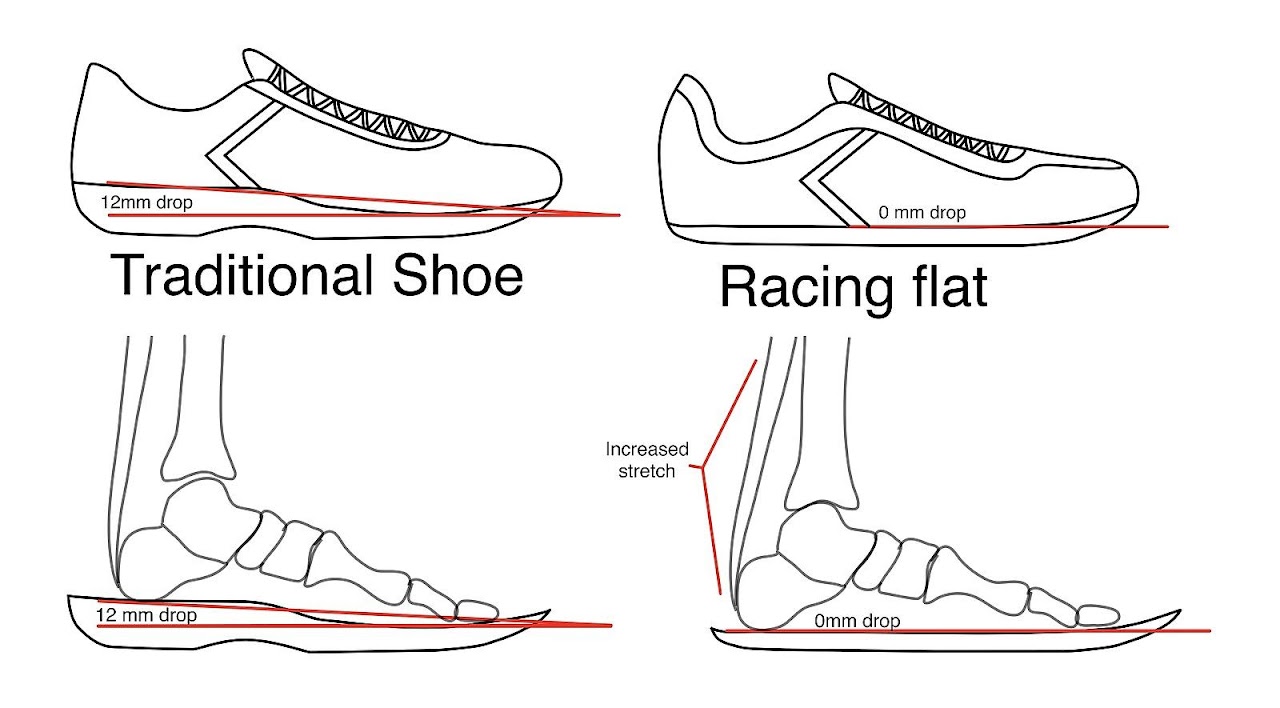

When you dive into the vast ocean of running shoes, a term you’ll likely come across is “drop.” If you’re not a seasoned runner, this term might be as mysterious as the dark side of the moon. In its simplest form, the “drop” in a running shoe, also known as the “heel-to-toe drop,” is the difference in cushioning height between the heel and the toe of the shoe, usually measured in millimeters (mm).

What is a running shoe drop?

In its simplest form, the “drop” in a running shoe, also known as the “heel-to-toe drop,” is the difference in cushioning height between the heel and the toe of the shoe, usually measured in millimeters (mm). It’s one of the critical features that differentiates one running shoe from another. An academic paper published by Esculier et al. in the British Journal of Sports Medicine (2018) stated that running shoe drop could significantly affect the strike pattern and running mechanics, influencing injury risk and performance.

The Different Types of Drop

Zero Drop running shoes, as the name suggests, have no height difference between the heel and the forefoot. This design aims to promote a natural running motion, similar to how our ancestors ran barefoot. Lieberman et al.’s Nature paper (2010) supports this, suggesting that humans ran comfortably and safely with a forefoot strike before the invention of shoes.

Low drop shoes typically have a drop between 1 and 4 mm. They still encourage a natural running style, but with a bit more cushioning than zero-drop shoes, providing a compromise between a traditional shoe and a barefoot running style. These shoes don’t have any real cushioning beneath the heel or forefront, and only a thin layer of material is between your foot and the ground.

Standard drop shoes, with a drop of about 10-12 mm, are the most common. These shoes have more cushioning in the heel, which, according to Nigg et al.’s research in Sports Medicine (2017), may encourage a heel-strike pattern, which some runners prefer for comfort or to match their natural gait. This heel-to-toe drop can correct problems that can occur in a person’s stride. An example of this would be an overpronator, or someone whose foot rolls inward as they walk. Someone with a problem such as this is more prone to ankle sprains, heel spurs, or Achilles tendinitis.

The Impact of Shoe Drop

Indeed, the impact of running shoe drop on a runner’s biomechanics and injury risk is critical. Higher drop shoes can lead to more running injuries, according to a study by Malisoux et al. (2016). Similarly, Cheung and Ng’s study (2010) showed that shoes with higher drops can cause a higher loading rate in the lower extremity, potentially leading to injuries like stress fractures and plantar fasciitis.

Meanwhile, the connection between biomechanics and running economy is not always straightforward. A lower duty factor, or ratio between contact time and step time, can improve running economy by aiding in the efficient storage and release of elastic energy in muscle-tendon units. In an intriguing study, Gijon-Nogueron et al. (2019) found that female runners wearing higher drop shoes had reduced contact and flight times, while lower drops increased these parameters. Therefore, choosing running shoes should consider individual needs and characteristics to optimize performance and prevent injury, highlighting the complex interaction between shoe drop, biomechanics, and injury risk.

Choosing the Right Drop

Choosing the right drop in a running shoe is crucial. There is no one-size-fits-all answer when it comes to shoe drop.

The choice of shoe drop depends on various factors:

Running style

Experience level

Personal comfort

Injury history

If you’re transitioning from a higher drop to a lower one, it’s recommended to do so gradually. This involves:

Changing shoe drop in small increments over time rather than making a sudden switch.

Allowing your body time to adjust to the new biomechanics introduced by a different shoe drop.

For example, if you are transitioning from a 12mm drop to a 4mm drop, start with a 10mm drop shoe, use it for several weeks, then move to an 8mm drop, and so forth. Paying attention to your body’s feedback during the transition. If discomfort or strain is experienced, it may be beneficial to spend a longer time at a particular stage before progressing.

In their 2014 article in the Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, Moore et al. provided support for this gradual transition advice.  Refs:

Refs:

Esculier, J. F., Dubois, B., Dionne, C. E., Leblond, J., & Roy, J. S. (2018). A consensus definition and rating scale for minimalist shoes. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(18), 1175-1182.

Lieberman, D. E., Venkadesan, M., Werbel, W. A., Daoud, A. I., D’Andrea, S., Davis, I. S., … & Pitsiladis, Y. (2010). Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners. Nature, 463(7280), 531-535.

Nigg, B. M., Vienneau, J., Smith, A. C., Trudeau, M. B., Mohr, M., & Nigg, S. R. (2017). The preferred movement path paradigm: Influence of running shoes on joint movement. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 49(8), 1641.

Malisoux, L., Ramesh, J., Mann, R., Seil, R., Urhausen, A., & Theisen, D. (2016). Can parallel use of different running shoes decrease running-related injury risk? Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 26(2), 202-208.

Cheung, R. T., & Ng, G. Y. (2010). Influence of different footwear on force of landing during running. Physical Therapy in Sport, 11(2), 45-51.

Moore, I. S., Jones, A. M., & Dixon, S. J. (2014). Mechanisms for improved running economy in beginner runners. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 46(9), 1756-1763